More than one-third of all animals on Earth, from beetles to cows to elephants, depend on plant-based diets. Plants are a low-calorie food source, so it can be challenging for animals to consume enough energy to meet their needs. Now climate change is reducing the nutritional value of some foods that plant eaters rely on.

Human activities are increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels and raising global temperatures. As a result, many plants are growing faster across ecosystems worldwide.

Some studies suggest that this “greening of the Earth” could partially offset rising greenhouse gas emissions by storing more carbon in plants. However, there’s a trade-off: These fast-tracked plants can contain fewer nutrients per bite.

I’m an ecologist and work with colleagues to examine how nutrient dilution could affect species across the food web. Our focus is on responses in plant-feeding populations, from tiny grasshoppers to giant pandas.

We believe long-term changes in the nutritional value of plants may be an underappreciated cause of shrinking animal populations. These changes in plants aren’t visually evident, like rising seas. Nor are they sudden and imminent, like hurricanes or heat waves. But they can have important impacts over time.

Plant-eating animals may need more time to find and consume food if their usual meal becomes less nutritious, exposing themselves to greater risks from predators and other stresses in the process. Reduced nutritional values can also make animals less fit, reducing their ability to grow, reproduce and survive.

Rising carbon, falling nutrients

Research has already shown that climate change is causing nutrient dilution in human food crops. Declines in micronutrients, which play important roles in growth and health, are a particular concern: Long-term records of crop nutritional values have revealed declines in copper, magnesium, iron and zinc.

In particular, human deficiencies in iron, zinc and protein are expected to increase in the coming decades because of rising carbon dioxide levels. These declines are expected to have broad impacts on human health and even survival, with the strongest effects among populations that are highly dependent on rice and wheat, such as in East and Central Asia.

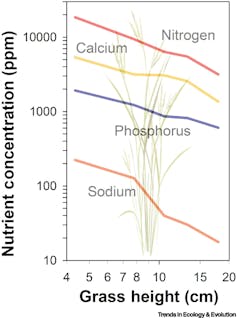

The nutritional value of livestock feed is also declining. Cattle spend a lot of time eating and often have a hard time finding enough protein to meet their needs. Protein concentrations are falling in grasses across rangelands around the world. This trend threatens both livestock and ranchers, reducing animals’ weight gains and costing producers money.

Nutrient dilution affects wild species too. Here are some examples.

Dependent on bamboo

Giant pandas are a threatened species with great cultural value. Because they reproduce at low rates and need large, connected swaths of bamboo as habitat, they are classified as a vulnerable species whose survival is threatened by land conversion for farming and development. Pandas also could become a poster animal for the threat of nutrient dilution.

The giant panda is considered an “umbrella species,” which means that conserving panda habitat benefits many other animals and plants that also live in bamboo groves. Famously, giant pandas are entirely dependent on bamboo and spend large portions of their days eating it. Now, rising temperatures are reducing bamboo’s nutritional value and making it harder for the plant to survive.

Mixed prospects for insects

Insects are essential members of the web of life that pollinate many flowering plants, serve as a food source for birds and animals, and perform other important ecological services. Around the world, many insect species are declining in developed areas, where their habitat has been converted to farms or cities, as well as in natural areas.

In zones that are less affected by human activity, evidence suggests that changes in plant chemistry may play a role in decreasing insect numbers.

Many insects are plant feeders that are likely to be affected by reduced plant nutritional value. Experiments have found that when carbon dioxide levels increase, insect populations decline, at least partly due to lower-quality food supplies.

Not all insect species are declining, however, and not all plant-feeding insects respond in the same way to nutrient dilution. Insects that chew leaves, such as grasshoppers and caterpillars, suffer the most negative effects, including reduced reproduction and smaller body sizes.

In contrast, locusts prefer carbon-rich plants, so rising carbon dioxide levels could cause increases in locust outbreaks. Some insects, including aphids and cicadas, feed on phloem – the living tissue inside plants that carries food made in the leaves to other parts of the plant – and may also benefit from carbon-rich plants.

Uneven impacts

Declines in plant food quality are most likely to affect places where nutrients already are scarce and animals struggle now to meet their nutritional needs. These zones include the ancient soils of Australia, along with tropical areas such as the Amazon and Congo basins. Nutrient dilution is also an issue in the open ocean, where rapidly warming waters are reducing the nutritional content of giant sea kelp.

Certain types of plant-feeding animals are likely to face greater declines because they need higher-quality food. Rodents, rabbits, koalas, horses, rhinoceroses and elephants are all hind-gut fermenters – animals that have simple, single-chambered stomachs and rely on microbes in their intestines to extract nutrients from high-fiber food.

These species need more nutrient-dense food than ruminants – grazers like cattle, sheep, goats and bison, with four-chambered stomachs that digest their food in stages. Smaller animals also typically require more nutrient-dense food than larger ones, because they have faster metabolisms and consume more energy per unit of body mass. Smaller animals also have shorter guts, so they can’t as easily extract all the nutrients from food.

More research is needed to understand what role nutrient dilution may be playing in declines of individual species, including experiments that artificially increase carbon dioxide levels and studies that monitor long-term changes in plant chemistry alongside animals in the field.

Over the longer term, it will be important to understand how nutrient dilution is altering entire food webs, including shifts in plant species and traits, effects on other animal groups such as predators, and changes in species interactions. Changes in plant nutritional value as a result of rising carbon dioxide levels could have far-reaching impacts throughout ecosystems worldwide.![]()

Ellen Welti, Research Ecologist, Great Plains Science Program, Smithsonian Institution

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.