Marc Zimmer, Connecticut College

In 2007, I served as a consultant for the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences’ deliberations about the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. As a result, I was invited to attend the Nobel ceremonies. Staying at the Grand Hotel with all the awardees, I got to see how scientists – excellent but largely unknown outside their fields – suddenly became superstars.

As soon as they’re announced annually in early October, Nobel laureates become role models who are invited to give seminars all around the world. In Stockholm for the awards, these scientists were interviewed on radio and television and hobnobbed with Swedish royalty. Swedish television aired the events of Nobel week live.

As a chemist who has also investigated how science is done, seeing scientists and their research jump to the top of the public’s consciousness thanks to all the Nobel hoopla is gratifying. But in the 119 years since the Nobel Prizes were first given out, only 3% of the science awardees have been women and zero of the 617 science laureates have been Black. The vast majority of those now-famous role model scientists are white men.

This is a problem much larger than simply bias on the part of the Nobel selection committees – it’s systemic.

Nobels still reflect another time

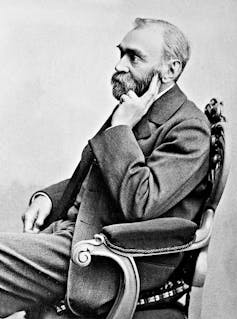

Five Nobel Prizes were established according to inventor Alfred Nobel’s will. The first prizes in chemistry, literature, physics and medicine were awarded in 1901. Each prize can be awarded to no more than three people, and prizes may not be awarded posthumously.

Just as with the Oscars for the movie industry, there is pre-Nobel buzz. Scientists try to predict who will be awarded the year’s chemistry, physics and medicine prizes. In the days and weeks following the announcement of the awards, there is a thorough analysis of the winners and their research, as well as sympathizing with those who were overlooked.

It doesn’t take a very detailed investigation to see that women and Black scientists are not proportionally represented among the laureates, that the United States is home to more winners than most countries and that China has surprisingly few science Nobel laureates.

Nomination to receive a Nobel Prize in science or medicine is by invitation only, and information about the nomination and selection process cannot be revealed until 50 years have passed. Despite this confidentiality, based on the list of laureates it’s clear that nominations tend to favor scientists working at elite research institutions, famous scientists who are good at self-promotion and those well known to their peers. Predictably, these tend to be older, established white men.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute are in charge of selecting the Nobel winners for chemistry and physics, and for medicine, respectively. They’re aware that they have a “white male problem,” and starting with the 2019 nominations have asked nominators to consider diversity in gender, geography and topic. One year in, it hasn’t yet been reflected on the dais. There were no Black or female award recipients in physics, chemistry or medicine at the December 2019 Nobel ceremonies.

So what’s going on? Why does the list of Nobel laureates seem to mirror the scientists of Alfred Nobel’s day more than the world in 2020?

STEM is more diverse than Nobels, but….

A 2017 National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics report shows that while white men make up only one-third of the U.S. population, they constitute at least half of all scientists.

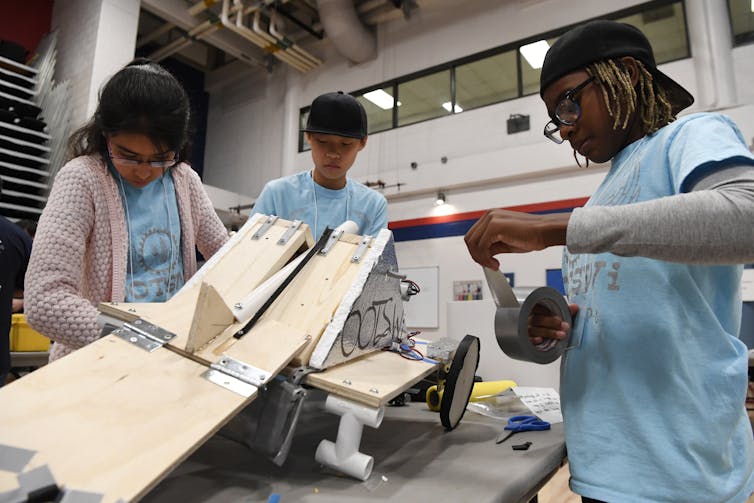

There’s no good reason students from underrepresented groups wouldn’t start out aspiring to careers in science, technology, engineering and math fields at the same rates as their nonminority peers. But minorities, who comprise 30% of the U.S. population, make up only 14% of master’s students and just 6% of all Ph.D. candidates. In 2017, there were more than a dozen areas in which not a single Ph.D. was awarded to a Black person, and these are primarily within the STEM fields. Only 1.6% of chemistry professors at the top 50 U.S. schools are Black. This gap hasn’t changed much in the last 15 years. There are not enough Black full professors in the sciences at elite universities where the networks and reputations critical for winning a Nobel are made.

There are many reasons for these dismal numbers: poverty, sub-par preparation in largely minority-serving schools of all levels and scarcity of role models and mentors. Stereotype threat, in which negative stereotypes lead to academic underperformance, can kick in, as can impostor syndrome, when a person feels inadequate despite evident success. Blatant discrimination and numerous microaggressions can also prevent scientists from minority groups from performing to their potential.

Though women make up more than half of the general population, they too count as an underrepresented group in many STEM disciplines. Just three women out of 213 physics Nobel laureates is obviously a disproportionately low number. Only five women have won in chemistry, and 12 in medicine. It’s hard not to think that many distinguished and immensely qualified female scientists must have been overlooked over more than a century of prizes.

The list of STEM Nobel laureates since 1901 sends the wrong message to young people, funding agencies, editorial boards and others about who does noteworthy science. Perhaps much more important, it is indicative of many biases and inequities that plague women and minorities in science. Colleges and universities host programs to support underrepresented groups in the sciences, but they are just Band-Aids on much bigger systemic issues in society. Without economic equity and educational parity, it will be hard to achieve Nobel diversity.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]![]()

Marc Zimmer, Professor of Chemistry, Connecticut College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The views and opinions expressed in the article are solely those of their authors, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of WomenInScience.com.