With a sharp increase in U.S. COVID-19 cases this fall and hospitals nearing capacity in parts of the Midwest and West, health care workers nationwide are scrambling to save lives – at great personal risk.

But the extraordinary number of people flooding U.S. hospitals has shined a spotlight on another crisis: the country’s nursing shortage. “While we have beds, those beds are only as good as the staff that you can place around them,” said Dave Dillon, a spokesman for the Missouri Hospital Association, quoted in the Washington Post.

High risk

The pandemic has created unprecedented challenges for nurses, including fear of workplace exposure. Since nurses have the most direct, hands-on patient contact, they face the greatest risk of infection of all health care workers. Many have been reassigned to the emergency room, “COVID units” or other high-risk departments.

It’s become an extremely dangerous job. More than half of the 20,000 nurses surveyed by the American Nurses Association last summer reported having to reuse single-use masks or treat patients with little or no personal protective equipment. Many are working 12- to 16-hour shifts. Some who have tested positive for the virus have been asked to continue working to care for the glut of patients. They face threats of physical harm from those who call the virus a hoax.

Some 36% of health care workers hospitalized with COVID-19 were nurses or nursing assistants, according to U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. As of September, 213 registered nurses had succumbed to the virus.

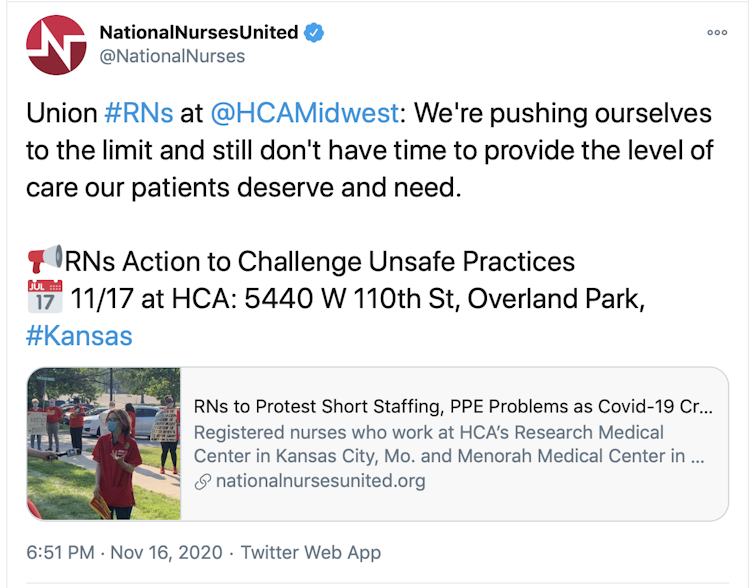

Working conditions have sparked protests in front of the White House and across the country. In May, the New York State Nurses Association filed three lawsuits against the New York State Health Department and two hospitals over safety.

The nursing crisis

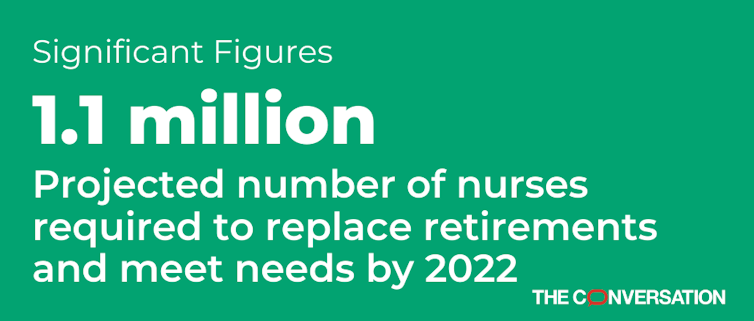

Some 4 million registered nurses make up the U.S. workforce; about 60% work in hospitals. By 2022, the nation needs 1.1 million new RNs to avoid a nursing shortage, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Hospitals can’t function without enough nurses, who spend more time caring for patients than any other health care professional. To keep hospitals staffed amid current shortages, some administrators are replacing nurses with technicians or asking nonhospital nurses to work in hospitals. These are life-and-death decisions: choosing either to treat patients under circumstances that could risk medical errors – or turn them away.

What caused this crisis?

My work as a nurse researcher and professor is to create a highly educated, competent nursing workforce and advance the impact of nursing on the health and wellness of our nation. I’ve found that current and projected shortages have many causes and vary widely, with the largest shortfalls in southern and western states.

Some of the looming problem is demographic. The average age of a U.S. nurse is 51, and 1 million nurses will be eligible for retirement in 10 to 15 years. Nursing schools are expanding, but it’s not enough to fill the void.

As the nursing workforce shrinks, the stress on the health care system is rising. The nation’s 73 million baby boomers are aging, with many suffering from chronic illnesses – such as heart disease, cancer and diabetes – that require intensive levels of care.

A dangerous, stressful career

Under normal circumstances, nursing is considered one of the most stressful careers. Demands of the job tend to take precedent over self-care; one study found that 68% of nurses put their patients’ health and safety before their own.

An American Nurses Association report revealed that the nursing workforce suffers from widespread health and wellness problems. Many nurses are overweight and don’t get adequate sleep; three-fifths work 10 or more hours a day.

The job places nurses at high risk of injury and illness. The dangers include moving and lifting heavy patients and equipment as well as exposure to infectious diseases, chemicals and radioactive materials.

Working under intense stress causes burnout in about half of all nurses. It may spark physical or emotional ailments, drug or alcohol misuse or depression. Nurses have a substantially higher risk of suicide than the general population.

Pandemic nursing

The health of the nation’s nurses needs immediate attention. Tired, sick burned-out nurses can’t provide the best care and are more likely to quit their jobs than those with better working conditions.

But now, the pandemic has made a tough job exponentially harder. It’s placed health care workers in war zone-like circumstances that they never trained for – or wanted. Picture the shock, for example, of a pediatric nurse relocated from the newborn nursery to a COVID-19 ward.

In a nationwide survey last spring, more than 60% of the 1,200 nurses interviewed said they were considering quitting their jobs – or leaving the profession altogether.

Rebuilding a strong nursing force

Without serious efforts to recruit more nurses and improve working conditions, the U.S. is in danger of serious breakdowns in the health care system.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

There are many ways to address the nursing shortage. Solutions include offering better salary and benefits, saner work hours and less physically demanding roles for older, experienced nurses to keep them working longer. Nonprofit initiatives like the “Healthy Nurse Healthy Nation” program can help improve health and wellness. Reaching out to youth and continued funding for nursing education under the Public Health Service Act will help spark interest in the profession and build a more diverse workforce.

A strong nursing workforce is essential to the health and wellness of the nation. Our health care system and our lives may depend on it.![]()

Rayna M Letourneau, Assistant Professor of Nursing, University of South Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The views and opinions expressed in the article are solely those of their authors, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of WomenInScience.com.