Jennifer Borland, Oklahoma State University

What type of images come to mind when you think of medieval art? Knights and ladies? Biblical scenes? Cathedrals? It’s probably not some unfortunate man in the throes of vomiting.

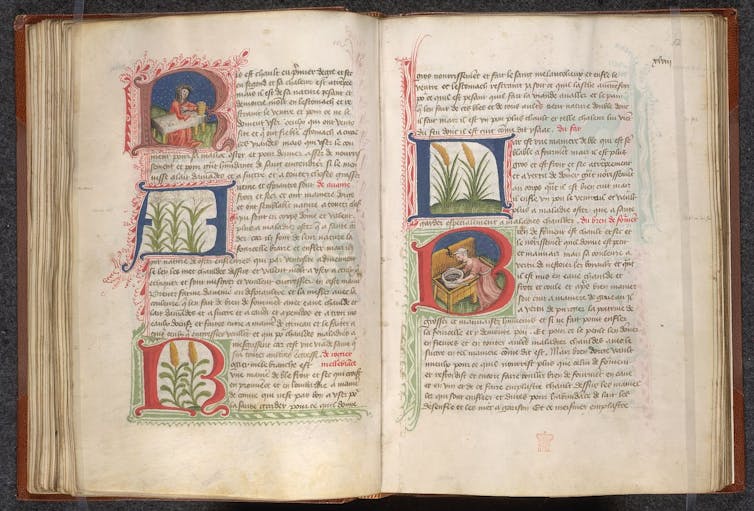

It might surprise you to learn this scene is found in a luxurious book from the Middle Ages made with the highest-quality materials, including abundant gold leaf. Known as an illustrated manuscript, it was made entirely by hand, as virtually all books were before the adoption of the printing press.

Why would such an opulent art form depict such a mundane topic?

Scholars believe that around 1256, a French countess commissioned the creation of a health manual to share with her four daughters just as they were forming their own households. Known as the “Régime du corps,” or “regimen of the body,” the book was widely copied and became extremely popular across Europe in the late Middle Ages, specifically between the 13th and 15th centuries. Over 70 unique manuscripts survive today. They offer a window into many aspects of everyday medieval life – from sleeping, bathing and preparing food to bloodletting, leeching and purging.

I’m an art historian who recently published a book called “Visualizing Household Health: Medieval Women, Art, and Knowledge in the Régime du corps” about these magnificent illustrated copies. What’s fascinating to me about the “Régime du corps” is how it depicts the responsibilities of women in wealthy medieval households – and how domestic management advice was passed down among them.

Glimpsing relationships

The illustrations, which are usually located at the start of each chapter, convey information not often found in other historical records. Even if the images are idealized, they reveal an extraordinary amount about the clothes, objects and furnishings of the period. They also show interactions among people that reflect the culture and society in which these books were made.

In a scene accompanying the chapter on caring for one’s newborn, two women are depicted opposite each other. Closer inspection shows the well-dressed woman on the right is reaching across and grabbing the exposed breast of the woman in more simple attire. This scene – seemingly one of aggression and violation – depicts the evaluation of a potential wet nurse.

Wet nurses were used throughout the Middle Ages by some elite families who could afford them, but choosing a good wet nurse was critical, loaded with life-and-death implications. Aldobrandino of Siena, the author of the “Régime du corps,” warns that an unhealthy nurse can “kill children straight away,” pointing to very real anxiety around this important decision. The different clothing and headwear communicate each woman’s social status. The elite woman’s gesture also makes clear who has the power in the scene.

Across “Régime du corps” manuscripts, upper-class women are presented with clothing, objects and gestures that convey authority, often in dialogue with those who are shown as laborers of various kinds. Servants within elite households are also illustrated, especially in the chapters about various foods and their health benefits.

Both men and women are shown sifting rice, making wine and managing livestock. The manuscripts’ creators chose not only to make such mundane and repetitive work visible but to treat the high-status physician and milkmaid as equally valid subjects for depiction.

Medieval health maintenance

In the Middle Ages, the health of family members, from infancy to old age, was maintained through a variety of strategies that aimed for balance in the body. The “Régime du corps” recommended a wide range of treatments, including the release of bodily fluids through purging or bloodletting to maintain such balance.

Cupping, or the placement of heated glass cups onto the skin, was among the procedures overseen by surgeons, because it involved scratching or perforating the skin before applying suction. Across “Régime du corps” manuscripts, it is not uncommon to see physicians and other male practitioners represented, implying that elite households made use of such professionals.

But women are also shown administering treatments, including in several cupping scenes. A practitioner’s humble clothing and headdress signal her class as a worker.

Such images show that medieval health care involved many tools – medicine, surgical treatments, food, prayer and charms – and a wide range of individuals offered their services both within and outside of the home. Women sometimes administered such care professionally, but they also did so through oversight of their own households.

The “Régime du corps” offered owners images that reflected their world – showing women asserting authority over the care of their families, providing treatment and contributing to a well-run household. The elite owners of these exquisite books were also provided with an added benefit: Possession of such manuscripts was undoubtedly a symbol of status and evidence of conspicuous consumption.

[Get the best of The Conversation’s politics, science or religion articles each week.Sign up today.]![]()

Jennifer Borland, Professor of Art History, Oklahoma State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The views and opinions expressed in the article are solely those of their authors, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of WomenInScience.com.